tv Great Decisions in Foreign Policy PBS September 10, 2010 8:00pm-8:30pm PST

9:00 pm

>> relations between the u.s. and china, in recent years, have focused primarily on one thing, the economy. but both countries have agreed to expand high-level talks to include issues of strategic importance. china's military buildup, north korea, taiwan, and climate change, are now all on the agenda. >> china wants to avoid real security crises. on the other hand, also, i think, it does aspire to be a great power in a very full way. >> how will dialogue between the u.s. and china shape the coming decade? next, on great decisions. >> in a democracy, agreement is not essential, but participation is. join us as we discuss today's most critical global issues. join us as we discuss today's most critical global issues. join us for great decisions. [instrumental music]

9:01 pm

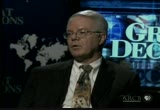

>> great decisions is produced by the foreign policy association, inspiring americans to learn more about the world. funding for great decisions is provided by the carnegie corporation of new york, the starr foundation, shell international and the european commission. great decisions is produced in association with the university of delaware. >> and now from our studios, here is ralph begleiter. >> welcome to great decisions, i'm ralph begleiter. joining us to discuss u.s./china relations and the rise of china's military, are david lampton, dean of faculty and director of the china studies program at the school of advanced international studies at johns hopkins university. and randall schriver, a founding partner at armitage international, and a former deputy assistant secretary of state for east asian and pacific affairs. welcome to you both. >> good to be with you.

9:02 pm

>> you know, it seems like every president since richard nixon, perhaps even ones before that, have struggled with the chinese/american relationship. it's just a tough one to deal with, and often it comes up very early in the administrations. why is that the case, randy? what makes it such a big uh, contentious relationship? >> well, i think it relates to the uncertainty of china's trajectory. uh, the questions still remain, ultimately, will china be more friend than ally, or more uh, adversary? and some of those questions are just not answerable. and i think, secondly, it relates to the complexity of the relationship. there's so much to it. so, there are positive aspects-- the trade and the economics are often viewed as more positive-- and then there are more challenging issues; security, human rights, non-proliferation. so i think it's those two pillars, really; the uncertainty of china's trajectory and the complexity of the relationship. >> david? >> well, i think one of the reasons you tend to have problems early on-- reagan had problems, and then george bush, the first, had tiananmen,

9:03 pm

uh, then george w. bush had the incident with the airplane on hainan island in 2001. >> spy plane landing... >> so it's been a pattern. i think it's interesting to observe and we'll see if it stays true, but thus far, president obama's administration's had a relatively smooth transition. anything can change. >> do you think the legacy of the relationship, on both sides, actually, has something to do with making it difficult to manage? in the united states, there are many, many americans who still perceive china as an enemy in a very, you know, old fashioned sense of being an enemy. and they think about vietnam and the vietnam era and all of that, uh, and the communist revolution and so on. and maybe in china, as well, the perception of the united states as being the enemy, with all of those years of propaganda that were disseminated. so is there a legacy thing, and is there anything we can do about that? >> i think legacy plays into it, and in particular, it tends to inform our campaigns, and in sometimes unhelpful ways, because a lot of those issues

9:04 pm

are seized upon in the course of campaigning for presidents for the presidency. and candidates often adopt a harder line during the campaign, and then they're sort of saddled with that when they come into government. we've seen several administrations have to do a little tacking back after they come into office. but yeah, i think the history informs our campaigns, informs the rhetoric as people are running for office, then we're stuck with that challenge of trying to move things back to a more sober place. >> you want to add something? >> well, i very much agree with that. and only would add that the chinese, of course, as you suggested, have their own legacy, and that was people's republic, 60 years ago, was founded and the united states initiated a policy for good reasons, a containment policy, and the chinese, to this day, still believe that there's a hidden strategic inclination in the united states to contain and slow down china's growth in order to maintain its dominant position. and that, combined with the textbooks that the chinese schoolchildren

9:05 pm

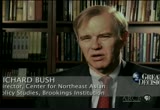

are educated with, certainly creates an environment of what i would call mutual strategic suspicion, and i think that's one of the most central problems we have in our relationship. >> i wanna talk with you about china's military position in the world, at the moment. but let's turn to some of our other experts that we spoke with at great decisions before coming to this program, see what they have to say, first. >> with respect to uh, china's military development, which is occurring at a steady and systematic pace, um, that does not challenge u.s. security per se. it does challenge, or maybe seem to challenge the security of our allies, japan, south korea, and our quasi-ally, taiwan. it also involves chinese military units, particularly air and naval, operating in areas that the u.s. navy used to see as its monopoly.

9:06 pm

and it was a forward extension of our forces that gave us a greater sense of security. now china wants to push out into the same area to improve its security. >> i think one of the issues for the chinese leadership is rising expectations, which is that if you continually talk about how china's becoming a great power, and you discuss uh, chinese military power, eventually the chinese people are going to expect you to use it, and at least be more assertive or forward leaning than the chinese have traditionally been. i think one of the characteristics of the chinese, foreign policy over the last two decades, has been to let other countries take the lead. and eventually, the chinese people are going to expect china to do more. >> china sees the western pacific as a place that's just more naturally its own than home to american submarines. and so these issues are going to have to be worked out, and the backdrop is rising chinese nationalism,

9:07 pm

which is something i-- that troubles me and i think is going to make it difficult for any chinese government to try to work through some of these issues. >> so let me ask you this simple question: is china expanding, aggrandizing its military in a way that threatens the united states? david? >> well, uh, i think the basic answer i would give is, not necessarily. whether it does in the future is going to depend on a lot of things. in part, the environment that the outside world creates for china. like mr. kristof, i worry about chinese nationalism. but i think the point that mr. bush made is the one that i would want to emphasize, and that is, traditionally, china's military power was based on a land army. when deng xiaoping came to office in 1978, china had four million, roughly, in its people's liberation army, mostly land troops, a very weak navy, and air force. deng xiaoping's approach was to reduce the land army and begin to build the army,

9:08 pm

or the air force and the navy. and by definition, that moves into the zones that the united states has traditionally occupied. china essentially began to want to be able to protect its increasing inter-dependance of the world. it gets 85% of its oil up through the south china sea, the straits of malacca. it wants to protect those resources, and so it's moved into the world. it's also acquiring the capacity to protect that. i don't think the conflict, military conflict, is inevitable, but i think we have to build some mutual strategic trust if we're to avoid it, and i think that's the core of the challenge that obama administration and its successors will face. >> you agree, randy, that it's primarily to protect china's own interests, in the pacific, for example, that is causing it to move in that direction? >> well, i would say it slightly different. i don't disagree with that comment, but i think some of what's been said by the commentators

9:09 pm

suggests that this is somehow not a concern for the united states because their capabilities aren't a challenge to us directly, maybe just to our allies and friends. but i think, in fact, if you look at the acquisition strategy and the capability that china is building, much of it is oriented against the united states. i don't say that in an alarmist way or to try to raise the specter of ah, coming adversary, but it's just plain fact, if you look at an acquisition strategy that includes anti-satellite weapons, anti-ship ballistic missiles, cruise missiles that are also aircraft carrier and ship killers, that were all procured after the '95, '96 crisis in the taiwan strait. much of this is about the united states. now, defense ministries all over the world prepare for bad outcomes, worst-case scenarios, etcetera. so i sort of come back to the point that the historical definition of threat, or at least we're taught in the military where i came from, is a combination of capability and intent. and so it's that intent side of the equation that is now uncertain that i think

9:10 pm

we can shape and work on and prevent this from being a relationship that heads toward uh, conflict. but there's no question in my mind that on the capability side of the equation, there's very robust, uh, investment, and much of it is oriented against the united states. >> you've had a good deal of military experience. i know there have been numerous efforts over decades, really, to engage in military to military cooperative exercises and discussions and so on. it doesn't seem as though much of that has succeeded. why? >> well, we've talked about the mutual suspicions and the overall relationship. that's at it's height, highest point, i would suggest, in the two ministries of defense in our militaries. and it's also the first part of the relationship that gets sacrificed when political relations sour. we pause or cancel the mil. to mil. aspects of the relationship. and so we've had a couple steps forward, and oftentimes, not just one step back, but two step back to the starting point. so it has been a source of personal disappointment, having worked

9:11 pm

on the military to mity relationship. but i think most analysts would say we're not anywhere near where we should be, in terms of our military to military interactions. >> david? >> well, i would say a couple things. first, from the capability side, we had also mentioned that china's had some impressive achievements in space, launched three different manned missions, and that's a whole 'nother zone of either potential cooperation or contention. and uh, so i think that's one thing we have to think about. also, cyber warfare, which is a whole new dimension, and actually some things happening from china. whether or not they all have the sanction of the chinese government is hard to say, but rather disturbing penetrations of our computer systems, and so forth. so that's a zone. i would say, though, that i think the chinese have tried to go to school on the soviet union. and the soviet union basically spent itself into oblivion on the defense side, undermined the support of its people, and scared the rest of the world

9:12 pm

to the point where we put a lot of pressure on 'em. i think the chinese do not want to go down that track, and so they're beginning to try to uh, engage in exchanges, not only with the u.s., that's been somewhat difficult, but with many other countries, many of our allies, countries in southeast asia, and so forth, you see the chinese inviting many of other countries, people to their academies and uh, military schools, and so on. so they're trying, on the one hand, to build up their capability, but on the other hand, be reassuring, and that's a very difficult tightrope toalk, and we'll see if they're successful. >> just a footnote on the space thing. i was going to ask you about that anyway. why is china engaging inhat space activity? is that a military focus, is it a matter of national pride, does it have to do with communication technology and the future development of china's uh, infrastructure at home? >> well, really, all of the above, actually. uh, i'll just give you one example, but there are both military and legitimate civilian,

9:13 pm

and it's often entangled. one of them was that china was highly dependent on the gps system of the united states, for guidance of aircrafts, civilian, military, and so forth. and uh, nonetheless, it did not want to be subject to being dependent on a system that, ultimately, the u.s. controlled. so it's been developing its own gps system at a rather substantial rate, would be one example. but china also has lunar missions planned for scientific exploration, for the most part. but china, as we have seen, also developing the anti-satellite weapons and so forth. and this is one thing, if you think about it, we cooperated with the soviet union in space at the height of the cold war. we have not been able to cooperate with the chinese to anywhere near that extent. and one reason is the military and civilian uses of space in the chinese program and the role of the chinese military in their space program is

9:14 pm

quite problematic for people in our security area. >> one of the areas where the u.s. and china actually do cooperate and have done so, really, for quite a few years, is on the very sensitive issue of north korea's moves in the direction of nuclear weaponry. let's see what some of our experts have to say about that north korea/u.s./chinese cooperation. >> both china and the united states, along with others, with face two big issues. first of all, how to contain a north korea that seems intent on keeping its nuclear weapons and has a reputation for reckless behavior. uh, second, this is not a partularly stable regime. nobody knows what will happen there when kim jong-il passes from the scene, but one cannot rule out the possibility of some kind of collapse. and in that scenario, the united states has certain interests,

9:15 pm

china has certain interests. >> i think north korea is one of these cases where the chinese have been fairly helpful. i think it brought north korea back to the table, several times. i think the larger issue, of course, is that china has an interest in uh, a denuclearized korean peninsula, but china also has an interest in stable borders and does not want a collapse of north korea. that is its primary interest. so there is going to be a limitation to how far ina will move with north korea, and the united states has run up into that. >> there's always been this sense in the u.s. that china has this, you know, magic leverage that all it needs to do is pull that lever and north korea will obey. that is simply not true. >> so i'm struck by, really, the contrast the way the u.s. and china have worked together on north korea over the years, and the way the u.s. and china have been unable, it seems to me, to work well on taiwan. what's the difference between those two conflicts?

9:16 pm

why has china been so willing to work with the u.s. on north korea? randy? >> well, i think we clearly have some common aversions, and i'm choosing my words carefully here, because it's not necessarily common interests. 'cause i think there is some divergence between the united states and china on north korea and the korean peninsula, but certainly some common aversions. uh, we both would not benefit if north korea remained a nuclear armed country with an expanding arsenal. we would both suffer if there was instability or a hard collapse that lead to chaos, and so forth. so, i think the sense of common aversions have given us a basis for discussion and some limited cooperation. but as some of the commentators noted, there are some limitations to the degree to which we can cooperate with china, and we're finding that through the course of this effort to cooperate with china. >> david? >> i think it's important to emphasize that if you ask in broad-brush, are we both concerned about proliferation?

9:17 pm

yes. are we both concerned about erratic north korean behavior? yes. but if you ask, what are our priorities? making the korean peninsula non-nuclear is not china's number-one priority. i think uh, keeping probably a buffer between south korea and china itself is an important chinese objective. most important to china is the northeast is a suffering economic region of china, and it does need poverty-stricken additional immigrants fleeing a breakdown or conflict in north korea. and therefore, the chinese will work with the united states beuse the mo important relationship they have, by their own account, is with us and they do share the anti-proliferation desire, but in the end, they are not going to push the north koreans anywhere near what they think the breaking point may be, because their priority interest is stability in north korea

9:18 pm

and not having problems that spill over into china itself. >> we can't have a discussion about china without at least touching on taiwan. it's a long-standing issue, perhaps the single issue that you can point to that's threaded through the entire sino-american relationship for all these decades. um, you know, and i think one of you mentioned earlier, that it was concern over taiwan--i think, randy, you said that in part, caused the chinese to build up their military capability. do the chinese really think that united states is going to go to war with china over taiwan? and why is that issue such an impossible to resolve problem between the two countries, between the u.s. and china? >> well, we have, i think, very different objectives. china's driven by their view that this is an issue an internal matter, and that really, it's an unresolved issue left over from the civil war that they believe is within their right to resolve. united states has developed an important relationship

9:19 pm

with taiwan, separate and apart from china, and it has included the foster of a very robust democracy in taiwan, a modern market economy, and so forth. and so, uh, for china, a very sensitive sovereignty issue for the united states. other things creep in, like democracy and human rights and a friendly relationship we've developed with taiwan. and so this has been particularly difficult. do they believe we might intervene militarily? well, there's language in our law, the taiwan relations act, that certainly suggests we might, because we have to maintain the capacity to resist force. the president would be required to report to the congress if there were a threat against taiwan and then convey what the plans would be to respond to that. and also, there's history. we did deploy two aircraft carriers to the region in '95, '96. if you go back even further, of course, in the 1950's, the chinese would very much blame the seventh fleet for preventing reunification after the civil war concluded in 1949. so yeah, i think it's something

9:20 pm

they remain concerned about. >> david? >> well, i think uh, i would agree with everything that was said. i would just add to the 1995, '96 crisis, i think the chinese were surprised by the magnitude of the american response. i don't think it was ever too much in risk that it would go out of control, but i think that they were surprised by the magnitude of president clinton's response at the time, which goes to show that once you get into a conflict situation, you can't always control each other's response, and i think that's the danger. but i would like to end this part of the discussion on a more hopeful note, and that is that we have a president in taiwan at this time, ma ying-jeou, who's made efforts, along with china's president, hu jintao, to kind of try to diffuse uh, tension in the taiwan straits. >> i think our other experts, as well--we asked them that same question-- agree with the idea that taiwan and other issues like that are not likely to bring the u.s. and china to war. let's see what they have to say. >> i don't think china wants

9:21 pm

to have any wars. it wants to develop itself economically. wars would be a distraction. it, you know, wants to avoid real security crisis. but on the other hand, it also does aspire to be a great power in a very full way. >> it's understandable that uh, china would want to secure its supply of natural resources from africa and other places, for that matter. it has become a leading manufacturing center in the world, and natural resources are what drive that. um, china, in effect, is replacing us as the key manufacturing center. what matters most for the united states is how china's quest for resources affects governments uh, in africa, and affects environmental protection. because, at least at the outset, china is pursuing this in a way that promotes corruption, promote environmental damage.

9:22 pm

>> i think the most likely conflicts that are going to come from china in this search for resources, are not going to be necessarily uh, conflict from the united states or any great power conflict. but i think what is happening already, that china's finding that when it deals with african countries or latin-american countries, that it faces the same problems as the european and u.s. faced in dealing with theses countries, in that many of them are unstable, many of them don't have complete control over their territory. many of them have insurgencies, and so china's efforts to say, well, we separate business from politics, it won't be tenable. they won't be able to continue acting in that way. and you can already see, in some states, um, that there's been a push-back. >> another area i want to touch on before we run out of time, is one mentioned by one of our other experts, and that is competition for resources. he mentioned energy in africa, but that's also going on the middle east as well, as china expands its interests there. is that an area

9:23 pm

where the united states and china will find themselves increasingly in competition for energy resources, perhaps other kinds of resources, not just in asia, but well beyond asia? randy? >> well, i think it's quite clear that china's consumption is going to continue to increase and so will ours, and so that puts us in the same space of needing energy. um, what's the real problem is--i think some of the commentators noted-- is the, if you could say, the externalities associated with that. china's support for some unsavory regimes, uh, their investment in these countries that does tend to breed and support uh, corruption. the fact that they're sort of taking a neo-mercantile approach to the acquisition of energy, when in fact there's very mature markets and these are fungible commodities, and so forth. so i think it's a space that we're going to both be occupying, and that also creates the possibility of cooperation, but there are second and third order effects to this that are going to be

9:24 pm

trouble soon and that we're going to have to deal with. >> david, you want to comment on that? >> well, i think the governance problems that both randy and the commentators pointed to are genuine. there's an interesting world bank report out that says, however, that chinese investment in africa, when much of the rest of the world wasn't investing in africa, had some plus aspects as well as the negative. i think we need to keep that in mind. the other thing is that the chinese now have what they call their going global policy, where, with its almost two trillion dollars in foreign exchange, it's beginning to invest in resource extraction. and in that sense, it's increasing the pool of oil and resources in the world through its investment, at the same time, it's representing some competition on the demand side. so, i would say this whole area of resources has its plusses and its minuses. >> david lampton, dean of faculty and director of china studies at the school of advanced international studies in washington at johns hopkins university, and randy schriver,

9:25 pm

a founding partner at armitage international and a former deputy assistant secretary of state for east asian and pacific affairs. thanks to both of you for being on great decisions. we appreciate it. and thank you, as well, for watching great decisions. we'll see you next week, i'm ralph begleiter. >> to learn more about topics discussed on great decisions, visit our website at greatdecisions.org. great decisions is available on dvd. to order, visit shoppbs.org or call 1-800-playpbs. funding for great decisions in foreign policy is provided by the carnegie corporation of new york, the starr foundation, shell international and the european commission. great decisions is produced in association with the university of delaware. next time on great decisions in foreign policy... >> when post-election rioting

9:26 pm

broke out in kenya in 2007, those responsible followed a familiar script. >> member states, they should be responsible to prevent and protect their own people. >> but this time, the global community was ready to act. bloodshed on a massive scale was averted. what lessons can be learned from the kenya exercise in early intervention, and what does it mean for an emerging doctrine at the united nations on responsibility to protect? >> next time, on great decisions on responsibility to protect? >> next time, on great decisions in foreign policy. [instrumental music] closed caption by captionlink www.captionlink.com

215 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

KRCB (PBS) Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11